The Audit Cycle

Posted on 23rd January 2018 by Saul Crandon

What is an audit?

Auditing is a vital part of clinical practice. An audit is an assessment of local practice and performance against an established standard. Essentially, clinical audit is a quality assurance and improvement process. It can be considered an exploration of what IS being done vs what SHOULD be done.

NICE definition of clinical audit:

“A quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change. Aspects of the structure, processes, and outcomes of care are selected and systematically evaluated against specific criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented at an individual, team, or service level and further monitoring is used to confirm improvement in healthcare delivery.”

Principles of Best Practice in Clinical Audit (2002, NICE/CHI).

How does it differ from research?

In short, research looks to acquire new knowledge whereas auditing does not.

Research looks into an explicit hypothesis and uses defined methods to generate results, with the aim to answer that question. In other words, ‘what is best practice?’. From research, a new drug may be developed, or perhaps a new service or a new way of managing a condition. As research deals with patients, it is necessary that it complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and gains ethical approval from a relevant Research Ethics Committee (REC). This comes under the practice of research governance, ensuring research is ethical, protecting both participants and researchers. On the other hand, audit looks to assess how well local practice is complying with best practice. Whilst audits should be carried out ethically, formal ethical approval from an REC is not required.

Research and audits serve very different, but necessary purposes. Smith summarises this nicely with the following quote from a 1990’s BMJ article:

“…research is concerned with discovering the right thing to do whereas audit is intended to make sure that the thing is done right.”

Smith R. Audit & Research. BMJ 1992; 305: 905-6 (1)

History

Florence Nightingale was thought to be one of the first auditors in healthcare in the 1850’s. At that time, she documented the particularly dirty conditions in the barracks during the Crimean War, noting that both morbidity and mortality was a significant burden. Following an increase in cleanliness and nursing care, she was able to reduce mortality by 38%, a pivotal finding that greatly supported Nightingale’s theories of promoting proper hygiene practices in patient care.

Why Audit?

There are many reasons to carry out clinical audits. Firstly, it is a necessary part of your duty as a clinician in the NHS. This is encompassed by the practice of clinical governance. Clinical governance is a range of activities that health professionals undertake to maintain and develop patient care standards (2). Other areas of clinical governance include Clinical effectiveness, Risk management, Education and training, Staffing, Patient and public involvement and Information Technology. Further discussions regarding clinical governance are beyond the scope of this article.

Auditing is also necessary to truly execute evidence-based medicine. The high quality research used to formulate guidelines is utilised effectively by ensuring that local practice conforms with best-practice ideals. This ultimately results in improvements in patient care and safety.

Local audits also allow national standards to be improved. The National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP) consists of over 30 national audits run by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) for NHS England. They feature the most common conditions that are present in clinical practice across the UK. Local data collection at various Trusts across England feed into the national audits to provide an overview of standards of care in these areas. These regular audits provide the local Trusts with individualised reports on their current practice and compliance with the chosen audited guidelines, allowing areas of improvement to be clearly identified.

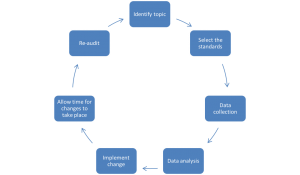

The Audit Cycle

The audit cycle is summarised in the diagram below:

- Identify topic

The topic must be an important issue as it underpins the entire audit. Examples of important issues include those that are high-risk for patients, high costs for the trust, areas of patient concern (which could have been collected from a survey) or areas of high volume workload. It is also necessary to register the proposed audit with the Local Clinical Audit Team and have it approved by the relevant Audit Lead.

- Select the standards

Select an established guideline (national or international) that is considered best-practice. Often the Royal College websites for different specialities have existing audit templates that are very useful. Extract the necessary targets from these guidelines (e.g. 100% of patients should be offered smoking cessation).

- Data collection

This can be retrospective or prospective. It may be beneficial to do this retrospectively to prevent performance bias from staff members that are aware of any prospective audit. Additionally, data can be collected from physical or computer records.

- Data analysis

Analyse the collected data and assess whether local practice meets guideline standards. Explore how well the standards were met and discuss any reasons for low compliance.

- Implement change

Present the results at local departmental meetings and possibly at local or regional conferences. Develop an action plan outlining what needs to be done and then create these changes!

- Allow time for changes to take place

It is important to allow sufficient time to pass for the uptake of new changes. Auditing too soon may underestimate the impact of new interventions, as they have not had time to take full effect.

- Re-audit

Conduct the audit again to assess whether practice has improved in light of changes from the previous audit.

How can I get involved in the audit process?

Get involved with your local hospital team – Identify areas of improvement through observation but also by liaising with the permanent staff – these doctors and nurses will be very familiar of areas that could be audited.

Register the audit with the Local Clinical Audit Team – this may be an online registration form, but it’s worth going in person to speak with the team. It’s useful to meet the Audit Lead to discuss the feasibility of the audit and whether they are happy to accept it.

Plan the audit rigorously – This includes thinking about what standards you will compare against, how you will collect the data and where the data will be disseminated.

There are many useful resources across the internet but in addition, local audit teams and healthcare professionals will have audit experience and should be happy for anyone to get involved.

References

- Smith, R. (1992). Audit and research. BMJ, 305(6859), pp.905-906.

- Scally, G and Donaldson, L. (1998). Looking forward: Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. BMJ, 317(7150), pp.61-65.