Do the outcomes measured matter to you?

Posted on 8th May 2018 by John Cafferkey

This is the thirty-first blog in a series of 36 blogs based on a list of ‘Key Concepts’ developed by an Informed Health Choices project team. Each blog will explain one Key Concept that we need to understand to be able to assess treatment claims.

When assessing a clinical trial, we know we should pore over the insightful and comprehensive introduction and background, underline the key objectives and squint a bit at the dense search methodology. If you’re adventurous, you may even have a go at pronouncing aloud some of the statistical tools the authors used. But all you’re doing is delaying the inevitable, instinctive desire to jump right in and find the answer. Of course, it’s good practice to glance at their neat flowchart and it’s only polite to consider what avenues the authors have suggested for future research, but deep down we really want the answer.

Welcome to the exciting, rewarding, racy realm of outcomes

An outcome is the particular effect we are measuring when we change something within a trial. Sometimes it is really obvious: if you were testing a weight loss treatment, you would want to compare the weights of people after they had had the intervention compared with the weights of those in a comparison group. The outcome you’d be interested in is the difference in the change in weights in the two groups.

In many cases, there are widely accepted outcomes that most people use in a particular field. This is really useful because it means you can assess different trials together (as long as their methods are sufficiently similar).

So how can we figure out what is an important outcome? Well, that depends on who you’re asking

However simple outcomes may sound, they are worth giving some serious thought. Different outcomes are important to different people. A doctor may think the most important outcome is mortality – if an intervention stops people from dying then that’s the main thing. A hospital manager may disagree: reducing admissions to hospital is the most important. Local government might be interested in how cost-effective this treatment is. Of course, if it matters to the patient, it’s important: so what if you can extend their life if they will be in awful pain the whole time? Will they want to take a pill for 30 years if it may only decrease their chance of a heart attack by a couple of percent?

This even occurs between different specialties: in palliative care, dying is not necessarily the awful outcome it may be in paediatrics.

Evidently, sometimes we have to compromise. Imagine carrying out a study where you had to compare one diabetes drug versus another. The reason we treat diabetes is because it has some really serious complications: eye problems, kidney problems and problems with your blood vessels (think heart attacks and venous ulcers). In an ideal world, we’d get two large groups of people, and give each group a different medication, and then follow them up over their lifetimes collecting data about the outcomes that matter: how long did they live for? Did they have any side effects from the medications? Did they have any eye problems to do with diabetes? Did they have any kidney problems? Did they have any heart attacks? We would take those data and compare the groups, to see whether one drug was better at preventing these outcomes. Unfortunately, that study would be very expensive, difficult to run and by the time we get the answers, we may have invented a new diabetes drug which might make our work obsolete!

So instead, we use surrogate outcomes…

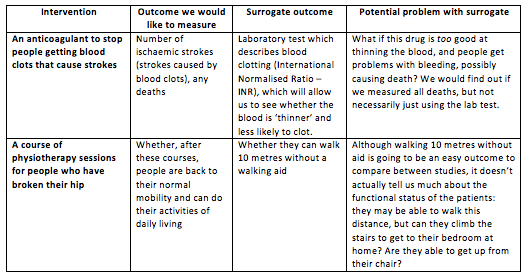

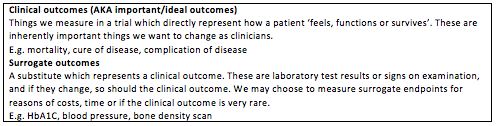

“Surrogate” literally means a substitute, something to take the place of something else. Surrogate outcomes are often laboratory tests, imaging studies or very tightly defined activities which we can use if the ideal outcome would be too expensive, rare or difficult to measure. The key assumption we make here is that we understand the underlying biology, and are certain that if this surrogate outcome changes, it means that the ideal outcome would change too. The table below puts it in context:

The main problem we see with surrogate outcomes is that they don’t always represent the ideal or important outcomes very well. Sometimes we find that even though a drug has the effect we want it to have on the surrogate outcome, when we use it on real patients we don’t get an improvement in the important outcomes. There are a whole host of reasons why this may be the case, but usually it’s either because we don’t fully understand the biology beneath these processes, or the drug may have other effects we haven’t considered.

To stress the point even further: we need to be very cautious of surrogate outcomes. Not only are they a bit rubbish in giving us the information we really want, but they can also sometimes be misleading.

To summarise:

Outcomes are usually intuitive and obvious. Be wary of surrogate outcomes. However, don’t dismiss a study because they use them – try to think about why the researchers may have chosen it. Always put yourself in the place of others: would this outcome be important to you if you were the patient? Finally, is there anything that these outcomes don’t tell you that you’d like to know – adverse effects, longer term impacts?

And finally, in answer to those questions at the top of the blog…

* Probably not: N=100, time to heal from partial avulsion surgery (partial removal of a nail) for honey dressings were 31.67 days (SD 18.8) vs ‘normal’ paraffin tulle gras dressing at 19.62 days (SD 9.31). That being said, if you have total avulsion (when all of the nail comes off) the results were far closer and the jury is still out. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16550669

**I’d be cautious: in a phase I study (in healthy volunteers) comparing the pharmacokinetics of colchicine (how the drug moves around the body) to treat gout whilst drinking about two cups of either grapefruit juice or Seville orange juice per day, the orange juice reduced the absorption of the drug and increased the time it took to get to its maximum serum concentration. However, there weren’t any significant adverse effects reported, and the authors stressed this may not be clinically significant. Interestingly, the grapefruit juice did nothing to the pharmacokinetics of the colchicine, despite the manufacturers warning strongly against it during treatment.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22940371

(Reference for definitions: FDA Archive documents – Clinical Investigator Training Course)