Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Posted on 6th December 2017 by Saul Crandon

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies are observational studies that lie near the middle of the hierarchy of evidence. These types of studies, along with randomised controlled trials, constitute analytical studies, whereas case reports and case series define descriptive studies (1). Although these studies are not ranked as highly as randomised controlled trials, they can provide strong evidence if designed appropriately.

Case-control studies

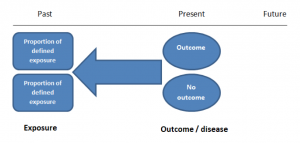

Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the outcome/disease and one without the outcome/disease. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups. See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of a case-control study design. This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is odds ratio (OR).

Figure 1. Case-control study design.

Cases should be selected based on objective inclusion and exclusion criteria from a reliable source such as a disease registry. An inherent issue with selecting cases is that a certain proportion of those with the disease would not have a formal diagnosis, may not present for medical care, may be misdiagnosed or may have died before getting a diagnosis. Regardless of how the cases are selected, they should be representative of the broader disease population that you are investigating to ensure generalisability.

Case-control studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their outcome / disease status.

As such, controls should also be selected carefully. It is possible to match controls to the cases selected on the basis of various factors (e.g. age, sex) to ensure these do not confound the study results. It may even increase statistical power and study precision by choosing up to three or four controls per case (2).

Case-controls can provide fast results and they are cheaper to perform than most other studies. The fact that the analysis is retrospective, allows rare diseases or diseases with long latency periods to be investigated. Furthermore, you can assess multiple exposures to get a better understanding of possible risk factors for the defined outcome / disease.

Nevertheless, as case-controls are retrospective, they are more prone to bias. One of the main examples is recall bias. Often case-control studies require the participants to self-report their exposure to a certain factor. Recall bias is the systematic difference in how the two groups may recall past events e.g. in a study investigating stillbirth, a mother who experienced this may recall the possible contributing factors a lot more vividly than a mother who had a healthy birth.

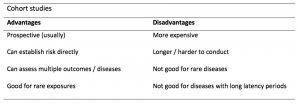

A summary of the pros and cons of case-control studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

Cohort studies

Cohort studies can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective cohort studies are NOT the same as case-control studies.

In retrospective cohort studies, the exposure and outcomes have already happened. They are usually conducted on data that already exists (from prospective studies) and the exposures are defined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a risk factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome development rate.

Prospective cohort studies are more common. People are recruited into cohort studies regardless of their exposure or outcome status. This is one of their important strengths. People are often recruited because of their geographical area or occupation, for example, and researchers can then measure and analyse a range of exposures and outcomes.

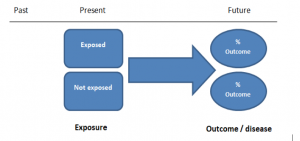

The study then follows these participants for a defined period to assess the proportion that develop the outcome/disease of interest. See Figure 2 for a pictorial representation of a cohort study design. Therefore, cohort studies are good for assessing prognosis, risk factors and harm. The outcome measure in cohort studies is usually a risk ratio / relative risk (RR).

Figure 2. Cohort study design.

Cohort studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their exposure status.

As a result, both exposed and unexposed groups should be recruited from the same source population. Another important consideration is attrition. If a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) then this may impact the validity of the study. Not only does it decrease the study’s power, but there may be attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study.

Cohort studies can assess a range of outcomes allowing an exposure to be rigorously assessed for its impact in developing disease. Additionally, they are good for rare exposures, e.g. contact with a chemical radiation blast.

Whilst cohort studies are useful, they can be expensive and time-consuming, especially if a long follow-up period is chosen or the disease itself is rare or has a long latency.

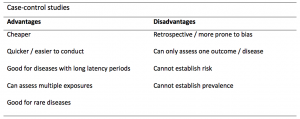

A summary of the pros and cons of cohort studies are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of cohort studies.

The Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)

STROBE provides a checklist of important steps for conducting these types of studies, as well as acting as best-practice reporting guidelines (3). Both case-control and cohort studies are observational, with varying advantages and disadvantages. However, the most important factor to the quality of evidence these studies provide, is their methodological quality.

References

- Song, J. and Chung, K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010 Dec;126(6):2234-2242.

- Ury HK. Efficiency of case-control studies with multiple controls per case: Continuous or dichotomous data. Biometrics. 1975 Sep;31(3):643–649.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453-14577. PMID: 18064739.

No Comments on Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Very well presented, excellent clarifications. Has put me right back into class, literally!

6th February 2023 at 4:30 pmVery clear and informative! Thank you.

5th December 2021 at 9:04 pmvery informative article.

8th September 2020 at 11:03 amThank you for the easy to understand blog in cohort studies. I want to follow a group of people with and without a disease to see what health outcomes occurs to them in future such as hospitalisations, diagnoses, procedures etc, as I have many health outcomes to consider, my questions is how to make sure these outcomes has not occurred before the “exposure disease”. As, in cohort studies we are looking at incidence (new) cases, so if an outcome have occurred before the exposure, I can leave them out of the analysis. But because I am not looking at a single outcome which can be checked easily and if happened before exposure can be left out. I have EHR data, so all the exposure and outcome have occurred.

10th July 2020 at 3:57 pmmy aim is to check the rates of different health outcomes between the exposed)dementia) and unexposed(non-dementia) individuals.

Very helpful information

17th May 2020 at 9:57 amThanks for making this subject student friendly and easier to understand. A great help.

5th April 2020 at 1:38 pmThanks a lot.

It really helped me to understand the topic.

I am taking epidemiology class this winter, and your paper really saved me.

Happy new year.

2nd January 2020 at 5:33 pmWow its amazing n simple way of briefing ,which i was enjoyed to learn this.its very easy n quick to pick ideas ..

11th December 2019 at 10:12 amThanks n stay connected

Saul you absolute melt! Really good work man

28th November 2019 at 5:04 pmam a student of public health. This information is simple and well presented to the point. Thank you so much.

31st October 2019 at 12:15 pmvery helpful information provided here

1st September 2019 at 6:07 pmreally thanks for wonderful information because i doing my bachelor degree research by survival model

12th May 2019 at 6:58 amQuite informative thank you so much for the info please continue posting. An mph student with Africa university

19th April 2019 at 4:57 amZimbabwe.

Thank you this was so helpful amazing

6th April 2019 at 7:43 pmApreciated the information provided above.

21st February 2019 at 6:04 amSo clear and perfect. The language is simple and superb.I am recommending this to all budding epidemiology students. Thanks a lot.

12th February 2019 at 3:31 amGreat to hear, thank you AJ!

12th February 2019 at 9:44 amI have recently completed an investigational study where evidence of phlebitis was determined in a control cohort by data mining from electronic medical records. We then introduced an intervention in an attempt to reduce incidence of phlebitis in a second cohort. Again, results were determined by data mining. This was an expedited study, so there subjects were enrolled in a specific cohort based on date(s) of the drug infused. How do I define this study?

7th February 2019 at 10:24 pmThanks so much.

thanks for the information and knowledge about observational studies. am a masters student in public health/epidemilogy of the faculty of medicines and pharmaceutical sciences , University of Dschang. this information is very explicit and straight to the point

14th November 2018 at 9:24 pmVery much helpful

15th August 2018 at 6:28 am