Reviews of fair comparisons should be systematic

Posted on 18th December 2017 by Benjamin Kwapong

This is the twenty-first blog in a series of 36 blogs based on a list of ‘Key Concepts’ developed by an Informed Health Choices project team. Each blog will explain one Key Concept that we need to understand to be able to assess treatment claims.

When it comes to treatments, we need to look for systematic reviews of all the evidence. Here’s why.

Suppose a new and exciting single study claims that a new treatment, let’s call it treatment A, can effectively treat condition B. Should the results of this one study be unreservedly trusted? No, they shouldn’t.

Why is this?

It is simple – and we need look no further than chance. It is likely that this presumed ground-breaking finding still occurred by chance, even if the number of participants and the outcome events were very large and the study was methodologically sound (which is often not the case). The result of the study may have been a fluke.

Relying on the outcome of this one study is a problem, and healthcare professionals and healthcare funders will not usually make decisions on the basis of a single study. Much evidence is needed as a basis for important decisions [1].

But what’s next, once there are plenty of studies?

Before we reach a decision, we need to critically appraise all the relevant studies to reach a conclusion about whether treatment A is effective for condition B. At this point we have two main options.

We can opt to do a narrative review (otherwise known as a traditional review), or a systematic review. Narrative reviews include searching for the relevant studies but the researcher does not prespecify which studies to include in the review, and why. For systematic reviews researchers specify in a protocol that defines ‘relevant studies’ are and it must include every study that ticks the boxes.

Unlike authors of narrative reviews, authors of systematic reviews should ideally register their protocol publicly and make explicit their criteria and how they reached each decision in their final paper. The detail provided should be sufficient to allow someone else to replicate the same review and assess whether similar results are obtained. As is clear, systematic reviews are perceived as more scientific and open to scrutiny than narrative reviews [3].

To make systematic reviews more informative it may be possible and appropriate to use statistical techniques, known as meta-analyses, to synthesise the statistical data from each of the studies. This yields overall estimates of the effects of the treatments compared [4]. You can learn more about this from Cochrane and systematic reviews.

Why systematic reviews are valuable

As with individual studies and as shown above, measures must be taken to reduce biases (systematic errors) and the play of chance (random errors), when doing reviews. Two other forms of bias result from preconceived ideas and who funds the research. These biases often sway the way we perceive certain outcomes.

In narrative reviews, there is much scope for bias as the researcher may include or remove studies that do not fit with their beliefs around the treatment, motivations or background. Effectively, they are free to do whatever they want and reach any conclusion that suits them and their interests. In systematic reviews, biases are not eradicated but measures are taken to reduce them. Researchers are open about what they do and expected to justify why they do it. With this information, we can have more confidence that their work is at less risk of bias.

Systematic reviews are not without problems, however. Like all research, they vary in quality and some are not trustworthy. Even if we replicate the review, different conclusions may still be reached. This may be because the review has not covered all the relevant research. Some studies may not have been included because they were not deemed sufficiently ‘exciting’ to be published. Academics as well as pharmaceutical companies may hide studies that do not fit their claims.

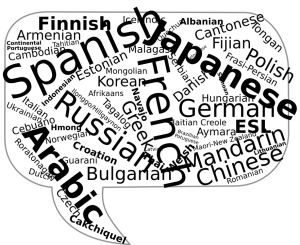

Language is also a barrier which may prevent certain studies being identified. For example, an English-speaking researcher may fail to identify relevant studies reported in languages other than English. Leaving out relevant research because it doesn’t support one’s claims is unethical, unscientific and wasteful.

For example, a healthy young laboratory technician, Ellen Roche, died in June 2001 after she accepted an invitation to participate in a study at Johns Hopkins University to measure airway sensitivity. The study required that she inhale a drug (hexamethonium bromide). This caused progressive respiratory and renal failure. It appears that the supervising physician, Dr. Alkis Togias, researched the drug’s adverse effects but limited his search for evidence to databases searchable back to 1966. It turned out that studies reported in the 1950s had warned about the effect of this drug and so her death should not have occurred [2].

Another example of the need to review evidence systematically and thoroughly comes from the treatment of people suffering a heart attack. In the 1980s, most of the recommended treatments for heart attacks in textbooks were, as expected, used extensively by doctors. However, it turned out that these recommendations were often wrong because they had not been based on systematic reviews of the evidence. Because the textbooks had not been based on systematic reviews of the relevant evidence, doctors were withholding effective treatments, and using treatments that were harmful [1].

Reviews are vital for informing healthcare decisions, but they must be done systematically.